MSD’s Project Clear and Our Local Water Issues

The Metropolitan Sewer District has been working hard on outreach to inform the public about Project Clear. In their own words, Project Clear is the “planning, design and construction of MSD’s initiative to improve water quality and alleviate many wastewater concerns in the St. Louis region.” MSD operates in both St. Louis City and County.

What are some examples of wastewater concerns in our region? Flooding, erosion, water pollution and sewer backups are some issues that affect many of our neighbors if not ourselves. MSD deals with both stormwater, which is intended to discharge directly into the natural environment, and wastewater, which needs to be treated at a wastewater treatment plant before release. MSD is undertaking large scale projects right now that are estimated to take 23 years to complete.

The budget for this work is 4.7 billion – the largest infrastructure investment so far in the history of our region. For official information about the project and about your own flood risk, see these resources:

- projectclearstl.org

- Project Clear STL on Facebook

- projectclearstl on Twitter

- Know Your Zone – Assess your risk and insurance needs

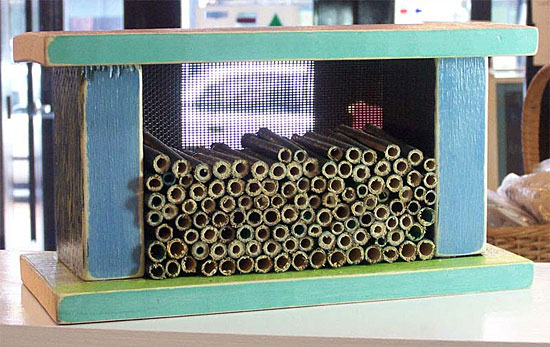

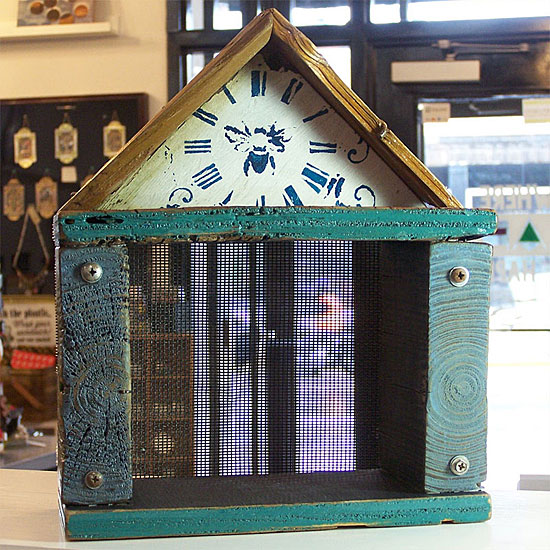

The first sewers in the St. Louis region were built in the 1850s. The amount of development present now is of course much greater than then and there are a lot more impermeable surfaces generating runoff. The existing system cannot cope with the demands being placed on it. MSD conducted a pilot program to test the effects of green infrastructure and came to the conclusion that the conversion of 400 acres from impermeable to permeable surfaces is equal to a 2 billion dollar savings in spending on wastewater infrastructure. Greenscaping has many other benefits – more oxygen, more pleasant and healthful surroundings, crime reduction, noise abatement, habitat for wildlife, temperature regulation – the benefits go way beyond just financial.

MSD is requesting help from the public with the wastewater issues they are working on. It’s in all of our best interests to do what we can to assist because the MSD projects are going to take decades to complete. Even if our own property is properly insured against damage, we will pay for water damage all over the region one way or the other in fees and taxes. In addition, cleaning up after a water disaster is no fun. It’s stinky, messy and time-consuming.

Some water management challenges are inevitable because of the geography and geology of where we live, but we all have the power to mitigate these problems by a small amount. If we each do a little bit we can help each other save money. What can we as individuals do to prevent erosion, flooding, water pollution and sewer backups?

- If your residential downspout is connected to your wastewater sewer line, disconnect it and direct the stormwater from the downspout elsewhere. My understanding is that this is going to be mandatory soon if it isn’t already so you might as well get started now. MSD will inspect your property on request to see if your downspout is improperly hooked up. Call (314) 768-6260 for assistance. MSD will pay the cost of disconnecting your downspout from the wastewater line. If you’ve ever thought that a rain garden or rain barrel was an intriguing idea, there has never been a better time to put one in! A rain barrel will help cut down on your water bill if you use it to water your garden, and natural rainwater sans chlorine and chloramines is better for your plants. Redirecting this water reduces the overload

on wastewater lines and prevents sewer backups. I suspect some of the downspouts at my condo are hooked up wrong and I know my neighbor whose unit is lower in elevation than mine has had a sewer backup before – so I find what MSD is saying about this credible. - Utilize rainscaping improvements on your property such as making surfaces water-permeable and protecting erosion-prone areas. There are rainscaping small grants available for residents in certain areas. Rainscaping has many benefits – prevents flood damage and erosion, improves water quality and recharges underground aquifers.

- Explore opportunities to re-use some of your gray water. This may also cut your costs because in some places you are charged for how much water goes out of your household through the sewers as well as for how much comes in – my understanding is that’s the case where I live. My water bill is included in my condo fee so I don’t see it but that’s what I’ve been told.

- Keep fats, oils and grease out of the sewer system by disposing in the trash and not down the drain. To help you remember here is a catchphrase – COOL it, CAN it, TRASH it. Improper disposal can cause sewer backups and water

quality problems. - Don’t use the sink or toilet to dispose of garbage.

- Use compost as much as you can in your landscape – compost absorbs water and slows velocity.

- Join a grass-roots effort to encourage the adoption of greenscaping and rainscaping practices.

- Join a stream cleanup sponsored by the Open Space Council,

River Des Peres Watershed Coalition, and others. - Join a volunteer storm drain marking project.

- Join a Stream Team.

Additional water management resources: